A life worth living, but for how long?

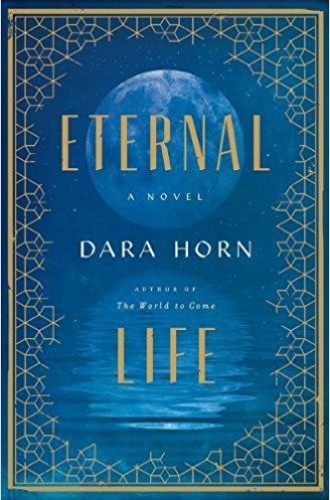

In their new novels, Dara Horn and Chloe Benjamin play with themes of mortality and free will.

Advertisers seem to want us to want immortality. “Hope lives here,” the trademarked slogan of the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, has been bouncing around my mind for three years now, ever since I regarded it while sitting in traffic on Interstate 676. The infant son of a friend’s friend had just been found lifeless in his crib after his afternoon nap, drowned in his sleep by the influenza virus before anyone even suspected he was ill. I had recently returned from Malawi, one of Africa’s poorest countries, and was suspicious of American optimism—particularly in its Christian form, which is quick to insist that God will provide (or has a plan or will heal).

It’s not that people in Malawi don’t pray for healing. It’s that Americans seem almost always to be caught off guard by misfortune, disease, or death and even, sometimes, genuinely offended at the idea that such things are unavoidable.

But what if death were avoidable? Novelist Dara Horn creates a fictional world in which immortality is shown to be a burden as much as a blessing. “What reasons are there for being alive?” asks Rachel, Horn’s immortal protagonist, after 2,000 years of marrying, birthing, nursing, tending, and burying everyone she has ever known and loved. She lists the usual reasons people give—to serve others, to experience joy, to build for the future—but feels (and argues, plausibly and beautifully) that these reasons break down for someone who has stepped outside of the typical game of birth, growth, and death. Horn is the mother of four children, and any reader who has cared for children for any length of time will notice how especially finely grained and insightful are Rachel’s observations on the nature and purpose of maternal self-sacrifice: “that first moment of holding your child, when your body became the gateway to the world, and from it, pure light.”