Should pastors and congregations seek to transcend politics or is that an impossible or even illegitimate goal? Is there a difference between being political and being partisan? We invited some pastors and theologians to respond.

Lee Hull Moses: In the past two years, our congregation has lost at least one regular attendee because we’re too political. At least one other left because we’re not political enough. Some folks wish we were out in force, wearing our church T-shirts, at every protest. Others wish I would tone it down from the pulpit and just preach about how to be a good person. I take some solace in the adage that if you’re making people mad, you must be doing something right.

Preaching’s gotten a lot tougher since the 2016 election, when even words like kindness seemed to have political implications and everyone retreated to their corners, boxing gloves at the ready. It’s complicated by the fact that “politics” has now come to mean any contemporary issue on which people might disagree. In times such as these, the preacher’s task is to remind the congregation that the basic tenets of our faith—grace and mercy, radical hospitality, love of neighbor—go beyond politics but have political implications.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

I wouldn’t be doing my job, I told more than one parishioner, had I not mentioned Charlottesville the weekend after Heather Heyer was killed by white nationalists in 2017. Can we call ourselves followers of the Prince of Peace and not condemn violence born of bigotry and hate? Likewise, I don’t see how we can read the story of Jesus welcoming the children and not have something to say about the migrant children separated from their parents at our southern border.

That said, it’s tempting to reduce the news of the day to memes and one-liners, served up readily on social media for the preacher rushing to finish her sermon on Saturday night. In these polarizing times, it’s easy to vilify the other side. In reality, hardly anyone who opposes gun control laws wants children to be murdered at school, they just think there’s a different way to keep kids safe. Most people who advocate for universal health care don’t want the government to take over our lives, they just want everybody to get the medicine they need. Good preaching in divisive times reminds people of the importance of nuance. It also reminds news-weary parishioners that their faith claims mean something about how they live in the world, that “being a good person” is directly connected to our political systems and structures.

For better or worse, I imagine my own congregation will likely stay somewhere in the complicated middle. I’ll probably keep annoying the folks who don’t think politics has any place in church, and the people who want to go to rallies will have to organize themselves most of the time. My prayer is that even as we disagree, we’ll stay true to the gospel call to welcome and to love.

Lee Hull Moses is pastor of First Christian Church in Greensboro, North Carolina.

James K. A. Smith: You might expect the obligatory nod to the challenge of preaching in our polarized climate—except for the fact that our congregations are comfortably partisan and have been engines of polarization, not some lingering holdout against it. Like our housing and education, Christianity reflects rather than resists what sociologist Bill Bishop calls “the big sort.” Congregations are predictable clusters of the politically like-minded. I expect that many pastors, whether on the left or right, can count on a certain slant of “us” and reliably decry a “them” on Sunday mornings.

So the challenge is less how to avoid upsetting ideologically diverse congregations and more a matter of rightly upsetting the monolithic congregations in front of us. But how? What does faithful political discipleship look like?

We don’t want to avoid being predictably partisan by falling prey to the illusion that the gospel is politically “neutral.” If some partisan stands align with biblical concerns for justice, we shouldn’t soft-pedal biblical themes just to avoid appearing partisan. Here’s a way the lectionary is a gift. These biblical themes confront us. Preaching isn’t dictated by the pet priorities of a party but by the worldwide curriculum of the body of Christ at worship. And some days, by grace, that Word will come as a challenge to our own preferences.

Nor does the unique “politics of Jesus” give us license to sequester ourselves in alternative communities. Policy is how we love our neighbors, and purity doesn’t release us from the Great Commandment. The illusion of being nonpolitical is a luxury of privilege that only leaves the vulnerable exposed.

With that in mind, I suggest two principles. The first is simple but hard: recover and renew eschatology. (As a refresher, I commend Fleming Rutledge’s new book, Advent.) The problem with the Christian political imagination today is not simply that it is predictably partisan but that it has ceded its elasticity and expectation to the here-and-now. We are all functional utopians who overexpect from the present and underexpect God’s sovereign grace. But the kingdom of God is something we await, not create. And while we hope for policy that bends the systems of society toward justice, we won’t legislate our way to the Parousia.

A second principle is related: we need to recover a wide-eyed Augustinian realism to counter cultural Pelagianism. Our utopianism is nourished by an overconfidence in our own powers and a blinding self-righteousness, coupled with a generic belief in the goodness of human nature (at least our human nature). The result is a political outlook that does not expect—or know what to do with—disagreement and disappointment, charging ahead with the frightening scowl of someone with good intentions. Mark Zuckerberg’s surprise at the ends to which Facebook could be put would never surprise an Augustinian. The Augustinian, knowing something of the human heart, would have planned for such dastardly machinations.

Which is just to say: we are waiting for another—doubtless very different—St. Reinhold.

James K. A. Smith is professor of philosophy at Calvin College and author of Awaiting the King: Reforming Public Theology

Susan M. Reisert: In divinity school I heard the pastor of a nearby church preach about an upcoming election, declaring in no uncertain terms how he believed the individuals of the congregation should vote on one of the issues on the ballot. I didn’t like the heavy-handed approach, nor did I appreciate being treated as if I hadn’t paid enough attention to the issues and how my faith informs my decisions. Over the years, I’ve thought about that experience many times.

While I occasionally feel called to preach about issues that are connected to politics, I try never to use the pulpit to advocate for a particular choice, as if faith can lead to only one answer or one way of voting on an issue.

Old South Church is a small congregation of well-educated and well-informed people that exemplifies something rare these days: a wide diversity of political perspectives. Yet somehow we manage to worship together Sunday after Sunday, supporting and encouraging each another on this journey of life and faith. Except for one or two who occasionally ask for more political material in worship, most people are looking for relief from the barrage of ugly and disturbing news. Regardless of one’s political affiliation, the back-and-forth political barbs that have become part of our daily lives are just too much.

I don’t believe that they are looking for an escape, exactly. They simply want something different, an opportunity that might offer a balm for their weary souls.

And that’s what I try to do. Although I often lift up justice and love, I endeavor to create a space for a little peace and quiet, reflection, consideration of the big picture, and renewal of our individual and collective relationship with our Creator.

There are plenty of politicians and clergy of various perspectives who claim that God is on their side. I am not one of those people. People of faith ought to recognize that to worship God is to know that we are not God. And, therefore, we do not know everything there is to know about the mind and desires of God.

Sunday morning worship should not be another place where we get our political ducks all lined up in a row. Worship is for praise and prayer, for singing and silence, for renewal of hope in a violent world, and a place to connect with what it means to be God’s people, appreciating that we can only barely glimpse the enormity and wonder of what that is.

Worship offers respite for the weary traveler, so that when worship is over, we can be the people we are called to be, sharing love and hope, even in—especially in—these difficult and challenging times.

Susan M. Reisert is pastor at Old South Congregational Church (United Church of Christ) in Hallowell, Maine.

William H. Lamar IV: Whenever we deploy words, especially in the service of God, we are acting politically. There is no such thing as nonpolitical language, especially when that language is bold to assert itself theologically, homiletically, or ecclesiologically. The church is a praying, singing, preaching, witnessing body. We witness to the in-breaking of God’s reign of love, justice, beauty, and abundance in time and space. We lament brokenness, evil, and violence. We proclaim that these dastardly realities are ending even as we groan and press toward God’s redemption of humanity and all of creation. Our prayers, songs, sermons, and testimonies are acts of political speech.

Servants of the church who claim that they are not political are indeed political. However, they are often servants of a politics contrary to a Christian understanding of God’s reign.

Our speech is political because it is the speech of God’s new creation. The church’s language is not spectator language. It does work, and it has work to do. The church’s language has the ambitious agenda of making all things new. And that is political.

My goal as a preacher or pastor is never to be nonpolitical. I bear witness through language and action that the God I serve is the author of the politics of abundance. There is more than enough of the physical, economic, and spiritual requirements for human flourishing in this nation and the world.

We cannot transcend politics. The gospel is a word that was used to declare the birth of a new emperor. Our speech heralds a new ruler, one hated by the Caesars and Herods who continue to kill innocents and crucify dissidents in an attempt to hold onto their power and thwart God’s reign.

I am not partisan. One political party often tracks more closely to my vision than the other. But both parties are woefully politically inadequate when measured against the politics of Jesus. They make decisions in the service of retaining power. When they do justice, it is done incrementally, and they are always wont to undo the little good that they have done.

We must be bold to advocate the politics of God’s realm in the church and outside of the church. I tell political leaders that we can afford good education in Washington, D.C., because God requires it. I tell elected officials that we can pay a living wage because God requires it. I organize to put pressure on Democrats and Republicans because theirs is the politics of expediency, ours is the politics of a new heaven and a new earth.

The church has often abandoned these politics for access and power. Like Jesus, and many of my ancestors in faith, I want to live and to die for the politics of God’s reign. If these politics do not animate our prayers, songs, sermons, and testimonies, our speech is reduced to sounding brass and tinkling cymbals.

William H. Lamar IV is pastor of Metropolitan African Methodist Episcopal Church in Washington, D.C.

Scott Anderson: I have recently returned to parish ministry after a 25-year hiatus, having served as a lobbyist in two state legislatures and at the federal level on behalf of the California and Wisconsin Councils of Churches. Because the bulk of my vocational work has been in the legislative arena, I regularly draw sermon illustrations from politics.

Like most mainline Protestant churches these days, we are a “purple” congregation, a mix of both Republicans and Democrats, though mostly Democrats, I suspect. Because I believe both political parties have contributed to our nation’s current political dysfunction, I regularly offer an equal-opportunity critique of the political arena. Our faith stands in judgment of our nation’s lawmakers—of whatever ideological stripe—when they fail to uphold the values implicit in the gospel demands for justice.

I do not use the terms progressive or conservative in my preaching and teaching because these are labels rooted in secular ideology and are not Christian terms. Reclaiming a Christian vocabulary as we talk about politics, which includes the fallibility of every political party or ideology or leader (i.e., human sinfulness), is one of the most important roles of the pastor, especially in our divisive political climate right now.

Any sermon I preach that mentions President Trump by name sparks a reaction at both ends of the ideological spectrum in the church I serve, and occasionally heated dialogue. Earlier this year I mentioned in a sermon that Trump’s tweet about the size of his nuclear button is antithetical to the gospel’s call for dialogue with the enemy, which resulted in some finger-wagging during the coffee hour that the pastor shouldn’t be talking about politics from the pulpit. But I always view criticism like this as an invitation for deeper dialogue and relationship, rooted in the divine gift of unity that binds us together as followers of Jesus. If we don’t talk about politics in the church setting, we are giving folks permission to compartmentalize their lives. Jesus Christ is Lord of all of life, including our political life, and that includes the decisions we make in the voting booth.

This year I have also preached twice on the subject of gun violence. In the adult forum following my second sermon on the subject, we were blessed with an unanticipated conversation across the political divide. Those in our congregation who are proud gun owners felt safe enough to speak up publicly for the first time, sharing their beliefs and experience with those in our church, including myself, who support greater gun restrictions. There was no arguing. People in the room started really listening to each other. It was a sacred moment

Scott Anderson is pastor of Westminster Presbyterian Church in Madison, Wisconsin

Stanley Hauerwas: Religion and politics do not mix. In particular they do not mix if the pastor uses the pulpit to lay down what she or he thinks should be said politically about, for example, American immigration policy or what we should think about what it means to “Make America Great Again.” It is difficult to preach against that slogan even if you really think what is really being said is “Make (White) America Great Again.” For preachers to use the sermon to declare their opinion on some issue can be seen as a violent act, given the presumption that the congregation cannot respond.

The only problem with “religion and politics do not mix” is that the phrase is one of the strongest examples we have of political rhetoric. There is no escaping “the political.” To refuse to take a political stance is to take a political stance. In particular, the presumption that the church is above politics underwrites the distinction between the public and the private that serves to relegate strong convictions, particularly if they are “religious,” to the private. Private, moreover, is the word we use to describe a fictive political agent, that is, the individual whose political views are to be respected no matter what they may be.

Moreover, the politics presupposed by the slogan “religion and politics do not mix” is issue politics of election years. “Issues” are what politicians use to distract “the people” from considering the fundamental injustices of our political arrangements. We assume we can concentrate on the issues because given that we are a democracy all we need do is vote. Christians take it for granted that democracies are the Christian form of government, though they seldom ask what makes democracies democratic.

So when Christians are in church they should be at their most political. But what is essential is how to avoid letting what passes as politics determine the political agenda of the church. Christians must learn again how to reframe issues in a manner that makes clear that the politics of Jesus is different. The church is its own politic, which means Christians cannot avoid being “political.”

For example, for Christians the issue of abortion is not addressed by naming whether we are pro-choice or pro-life but rather by asking: What practices are necessary to be a people who trust we have gifts worthy of passing on to future generations? It may come as a surprise to many that having children entails a politics. But if it is a surprise, that is an indication of why it is so important for the church to reclaim the very existence of the church as a politics.

Stanley Hauerwas is author most recently of The Character of Virtue: Letters to a Godson

Sandhya Rani Jha: My mind has been on the French village of Le Chambon recently. During World War II, the village of maybe 5,000 people saved possibly as many as 5,000 people from the Nazis and the Vichy regime. As President Barack Obama noted on Yom HaShoah/Holocaust Remembrance Day in 2009, “Not a single Jew who came [to the area of Le Chambon-sur-Lignon] was turned away, or turned in. But it was not until decades later that the villagers spoke of what they had done—and even then, only reluctantly. ‘How could you call us “good”?’ they said. ‘We were doing what had to be done.’”

In my current itinerating ministry, I have visited a lot of churches that are proud of their commitment to being nonpolitical because it makes them more inclusive. But a nonpolitical church’s politics supports the way things are. That doesn’t make it an inclusive church. It makes it a church that is unwelcoming to people who want a different world. To riff off of a popular meme from the height of the Black Lives Matter movement, people of color are saying to the mainline church, “The American empire is literally killing us,” and the mainline church is saying, “Yes, but . . . ”

The reason Le Chambon keeps showing up in my imagination is this: every Sunday for over a decade before France fell to the Nazis, the pastors of the village preached a message that reinforced their community’s identity and what that identity meant in practice. The message was:

- We are Huguenots who survived persecution by the Catholic majority. That means we show up for people being persecuted.

- We are Christians. This means engaging in nonviolent resistance to empires doing harm and protecting the people who are being harmed.

In a sermon delivered the day after France surrendered to the Nazis, village pastor André Trocmé said to his congregation, “The responsibility of Christians is to resist the violence that will be brought to bear on their consciences through the weapons of the spirit.”

That is not an inherently political message, but it is a message that demands people act out of a certain ethic. In the late 1930s, the village protected political refugees fleeing Franco in Spain. Throughout World War II the people of the village protected Jewish refugees, even though it put their own lives and those of their families at risk.

Jesus resisted an oppressive empire in ways both overt and subversive. His message wasn’t inherently political, but it was a message that demanded people act out of a certain ethic. In these days, as in all times when people are suffering, a church that is proudly nonpolitical would be well served to reflect on what it means to reinforce the best part of a community’s identity and what that looks like in practice.

Sandhya Rani Jha is founder and director of the Oakland Peace Center.

Peter Bouteneff: When committed Christians are asked to weigh in on politics—especially as politics bear on morality—we speak about “the values of the gospel.” With this, we are really talking about Christ values. And that entails identifying who Christ is, what he does, and what he teaches us. Who is Christ? He is the God-man: the eternal Son of God who becomes human. What does he do? He lives among us as a human being and suffers the full consequences of fallen human society, all the way up to his death—which became a path to our eternal life.

Now let’s consider what he teaches us. Christ values are set out plainly, in Matthew 5–7. Those are the commandments that spell out the love of God and neighbor for all its implications as we live our lives. Christ’s identity, actions, and teachings converge: Love, to the end. Cultivate and preserve life. Check your anger and lust. And if we want to see further how these principles are to be lived out, we can look at Matthew 25:31–46.

So how would these principles be spelled out when it comes to American political parties and political issues? Let’s take two of the more urgent issues as examples: poverty and abortion. I would suggest that while the gospel is clear on the goals—the redressing of the rich-poor index, and the reduction of abortions—it does not prescribe the means of attaining them.

Do we redress poverty and care for the poor primarily through individual charitable giving and service—or primarily through tax-funded, government-administered programs? Do we reduce abortions by making them illegal—or by changing the culture: persuading people that life in the womb is life and addressing the social and economic conditions that account for the highest concentration of abortions?

The gospel obviously couldn’t have envisaged the political systems in place in the United States today. “Gospel values” do not prescribe for us how to shape our governments. They tell us how to live. This leaves us with the responsibility to make our political decisions on the basis of our best judgment as to which actions will yield the most life-giving results. Many Democrats, and many Republicans, feel with great conviction that their choice is the truly Christian one, but let’s face it: neither party today truly and fully embodies Christ values, and neither presents the only right solution.

Our secular political culture feels less and less inclined toward respectful dialogue and creative political thinking. Our church culture sometimes feels just as divisive. This is a time for us in the church to come together, across political disagreements, to articulate and reaffirm the Christ-centered goals that we do share, even as we will argue reasonably and prayerfully for different ways of reaching them.

Peter Bouteneff is professor of systematic theology at St. Vladimir’s Orthodox Theological Seminary.

Rob Schenck: As an itinerant preacher for more than 40 years, I’ve visited over 1,000 pulpits across the United States, representing just about every brand of American evangelicalism. As an activist on the religious right for most of those years, many of my sermons were highly politicized.

But then something happened. In my early fifties, I undertook doctoral studies on the German church struggle during the rise of Nazism. I went on to examine the political trajectory of evangelicals in the United States. The result was a dissertation discussing the problem of political idolatry among American evangelical pastors. I came to see grave danger in political pulpit content.

Still, I do not advocate for apolitical sermons. Instead, I advise fellow pastors to approach political subjects with great caution, contemplation, and consideration for the spiritual, social, and relational needs of their flocks.

The pulpit is not a place for a minister to flippantly air narrow, personal opinion on anything, especially politics; it is a place to form disciples, strengthen bonds, and announce the gospel.

So how does a preacher deal with the political and remain faithful to the Christ who seemingly eschewed a political interpretation of his mission? I recommend implementing a careful and prayerful vetting process. First ask, What is my purpose? If the answer is tied to a political outcome, ask, How does this outcome reflect the transcendent, the supernal, the universal? How will this sermon make new Christians, better form existing Christians, or project God’s love and benefits to the whole of humankind?

When it comes to the political, we must also ask, What is my source of guidance on this subject? Political opinions are often temporal, earthy, and narrow, not to mention divisive. Before preaching a sermon with political implications, the preacher needs to settle what informs his or her political thinking, viewpoint, and passions. For evangelical preachers, the sermon must follow from a clear biblical mandate; it must be consistent with the teaching and model of Jesus; and it must advance the “good news.”

Political questions are often good ways to get at the moral, the ethical, even the spiritual. For the sermon to stop at a political end is to truncate its potential. Politics, at its very best, reflects our principles, values, convictions. Like Jesus and the Roman coin, political responsibilities point to greater obligations: “Render to Caesar what is Caesar’s, and to God, what is God’s.”

Rob Schenck is president of the Dietrich Bonhoeffer Institute in Washington, D.C., and author of Costly Grace: An Evangelical Minister’s Rediscovery of Faith, Hope and Love.

Teresa Hord Owens: I serve a denomination whose heritage is grounded in an embrace of theological diversity. We live in the tension of difference, believing our witness of unity to be more powerful when we find a way to minister together despite differences. In today’s divisive political climate, the ability to engage not just civilly but respectfully requires a theological framework that focuses on a unity that is, as a noted Disciples theologian says, not a human agreement but a gift from God. Living into unity does not mean that one cannot speak one’s mind, only that one seeks to respect those with whom one differs, holding the gospel of Jesus Christ as the ultimate value and believing that living into the tension that unity requires is a reflection of Jesus Christ’s boundless love.

As Christians, we are often comfortable addressing daily human needs but not so comfortable in speaking to the systemic injustices that are at the root of the problem. When we talk about “justice” rather than “mission,” many will be uncomfortable, saying that the church is being “political.” And yet some would argue that addressing these unjust systems is indeed evangelism, and a witness to the love of God for all.

All of these perspectives are present within our church, and I seek to respect all voices, even those with whom I disagree. I argue for biblical literacy and spiritual disciplines as a way to build a theological foundation that allows for unity in the midst of theological diversity. That we might all bear witness to the love of Jesus Christ despite those differences is, I believe, the heart of the gospel.

As Christians, our work must always be theologically grounded and focused on aligning what we do with the command of Christ to love one another as he has loved us. Spiritual disciplines such as prayer and Bible study help us to articulate how we understand God’s call to follow the example of Jesus Christ. When we speak, we must speak from that theological grounding, not from loyalties to tribe or politics. We are on dangerous ground when we identify a particular theological perspective as “American” or when we insist that only certain political positions are “Christian.”

We serve, we advocate, we speak in accordance with an understanding of the teachings of Jesus, even when we struggle and disagree with specific interpretations of text or teaching. Within our church, we seek to ensure that all voices are heard. If we start with love, we will understand that the way in which we engage one another, even when we disagree, is a hallmark of Christian discipleship. These commitments to love and diversity can enable the church to model faithful engagement with the world’s concerns that respects the humanity and dignity of all.

Teresa Hord Owens is general minister and president of the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ)

Matt Croasmun: Discerning the way of Jesus is challenging in any time. It is more so in our day when political discourse threatens to drown out all other modes of reflection.

The challenge is that political discourse and theology both have to do with discerning the shape of the good life—the flourishing life we ought most desire for ourselves, our communities, and our world. In our polarized political climate, the ever-present temptation is to reduce our theological discernment of flourishing life—our seeking of the kingdom of God—to a vote for one of two political visions. This is the way of partisanship. A second option is to assiduously avoid “political” talk altogether. When we do that, we strip the gospel down to a privatized husk: theological individualism bereft of God’s intentions for the whole creation.

Both partisanship and quietism aim to save us from the theological work of discerning the good life; that is, they aim to rescue us from the burden of being the church. Only by owning our ecclesial responsibility for theologically discerning the good life can Christians relate rightly to politics.

It was a commitment to that kind of discernment in 2016 that led me to join other pastors and leaders of local mosques at a meeting with our city’s black, Christian police chief and a black, Muslim police sergeant. The topic was race, Islamophobia, and policing—and how together we might discern ways for our community to flourish.

It was another effort at discernment that led members of my congregation on a listening trip to Baltimore during the protests following the death of Freddie Gray, who died while in police custody. We have listened for the voice of Jesus during weekly meetings with police. And we have listened to one another, as when a church member confessed the sin of her instinctive fear of unfamiliar black men—the same fear that led police to take black lives. We mourned with our Muslim neighbors as they weathered threats against their mosque. We stood with them—and with the police—against Islamophobia.

The work of theological discernment leads us to strange places, standing against police brutality while nevertheless engaging the police as community partners. It leads us to stand with our Muslim neighbors because of—not in spite of—our passion for Jesus.

And we get things wrong. We move too slow. Or we move too fast. We do the right thing for the wrong reasons—and vice versa. There is no great victory to report.

Perhaps this fallibility most starkly distinguishes theological discernment from political ideology. Political pundits—both paid and pretend—win points at all costs. Theologians pray time and again: “Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on us sinners.”

Nevertheless, we earnestly seek the true life. We listen, we discern, and, always imperfectly, we seek to follow the One who proclaims and demonstrates a kingdom beyond—but not apart from—politics.

Matt Croasmun is pastor at the Elm City Vineyard church in New Haven, Connecticut, and associate research scholar at the Yale Center for Faith and Culture at Yale Divinity School

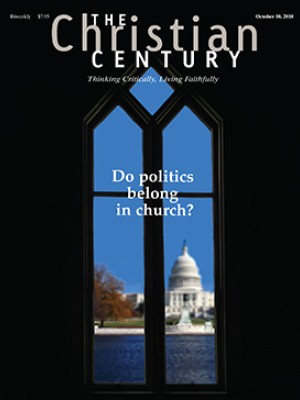

A version of this article appears in the print edition under the title “Do politics belong in church?”