A pair of museums are reckoning with Mississippi’s racist past

But they don't say enough about racism in the present.

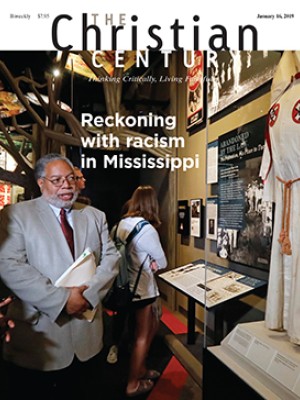

If a set of museums could represent what historian Ibram X. Kendi calls a “dual and dueling history of racial progress and the simultaneous progression of racism,” the Mississippi Civil Rights Museum and Museum of Mississippi History, which opened side by side in December 2017, just might be it. Two speeches given within one year on the museums’ shared grounds help to reveal this continuing tension in the state of Mississippi and the soul of our nation.

At the close of the November 2018 runoff election for a U.S. Senate seat, Mike Espy stood in the Civil Rights Museum and voiced hope that “Mississippi’s future will be brighter than Mississippi’s past.” Had he won, Espy would have been the first African American senator from Mississippi since 1868. Instead, Cindy Hyde-Smith, who’d joked about attending a public hanging—claiming ignorance of the racist implications of such a statement—won the election. Hyde-Smith, who also spoke in favor of voter suppression and was photographed wearing Confederate regalia, won with the strong endorsement of President Trump. At the opening of the museums a year earlier, Trump had read a prepared speech in which he strayed from his notes only to say, “I do love Mississippi, it’s a great place . . . I’ve had a lot of success in Mississippi.”

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Last September, I visited these two new museums in Jackson as part of a series of road trips I’ve been making throughout the South. As a biracial Christian raising my family in the rural South, I’ve been trying to put my fingers into the wounds of racism. I wondered how a state like Mississippi—with a legacy of extrajudicial, racially motivated killings and systematic refusal to extend voting rights and equal access to education, employment, and housing to African American citizens—would be able to accurately curate its shameful past or address current racial divides.

I found in the two museums, which share a common entrance and foundation, a unique gathering space for unprecedented, state-funded truth telling about centuries of enslavement and disenfranchisement, but I also sensed a hesitancy to describe current racial disparity. Visitors can simultaneously lament the cruelty of the state toward its people and celebrate the courage of people who persevered to change the story. Through moving videos and recordings of oral histories, meticulously researched interpretations of events, articles, photos, and artifacts, both museums allow the stories of Mississippi to be told in ways that, thus far, no other state has been as vulnerable in telling. Just as Jesus indulged Thomas by letting him put his fingers into his nail-pierced body, Mississippi’s museums are doing powerful work to shed some light on very deep wounds. What is less clear is the state’s willingness to acknowledge the wounds that continue to be inflicted.

The architecture of the museums seems to embody the tension between empire and resistance. The civil rights museum, which covers the decades from 1945 to 1976, has a wheel design centered on a common atrium. Its angles and curves suggest modernity, synergy and creative movement. In contrast, the history museum, which covers the millennia from 13,000 BCE to the present, is split into two floors and has a more linear design. Its large exterior columns might look stately to some, but to me they felt like a menacing reminder of stateliness at its worst.

I asked the director of the civil rights museum, Pamela Junior, why the museums are so different from one another. She responded that they are not two museums and that people must visit the history museum to understand what led to the civil rights movement. When I pressed her on how a state with such a bad track record could honestly share space with the stories of those who resisted it, she added, “Mississippi is a great place, it is not a backward state.” As a Mississippi native and an African American woman, Junior feels a deep indebtedness to the veterans of the movement who helped to make her state feel like a place where she is thriving. She sees it as a tremendous gift and responsibility that she has been entrusted to curate the “biggest classroom” in the state. “It is a testament to the state,” she asserts, “that they have chosen to take the bandage off a wound that has been festering for years.”

It was not a bandage but a roof that blew off the old Museum of Mississippi History during Hurricane Katrina that prompted conversations about rebuilding and sharing space with a new museum of civil rights. Founded in the tumultuous year of 1968, the history museum had proudly displayed the largest collection of Confederate paraphernalia in the country. By the time Katrina hit in 2005, a fresh telling of Mississippi history was long overdue.

Meanwhile, Mississippi activists had been planning a civil rights museum for decades but needed funding and space. After more than a decade of planning, the two museums were built together using $90 million provided by the Mississippi legislature and an additional $19 million from private donors. The shared space is a symbolic way to unite disparate narratives in the hope of a shared future.

The history museum has all the wigged mannequins and dioramas of a classic old museum, as well as the collection of artifacts meant to preserve the Lost Cause narrative. But there is a fresh honesty in the words that describe the state’s history and a sense that the story is still unfolding. The museum goes beyond black and white, weaving in the stories of Southeast Asian, Latinx, Choctaw, and Chickasaw people and people of various faiths who call Mississippi home.

Rachel Meyers, the director of the history museum and a member of Mississippi’s small Jewish community, has embraced the challenge. “All the ills are on the walls,” says Meyers, “very publicly in ways that no other state history museum has done.” A bone-chilling 1903 quote from Governor James K. Vardaman leaves no room for interpretation: If it is necessary every Negro in the state will be lynched; it will be done to maintain white supremacy. Meyers says she knows the museum is “doing something new and important” because at least twice a month, a visitor will come to her angry that they are aren’t getting a romanticized narrative of a good old Mississippi.

Yet the history museum does not directly engage current controversies like mass incarceration, police violence, or racist symbolism. For example, Mississippi is the only state that still has the Confederate battle flag embedded in its flag design. In 2016, Mississippi rejected a lawsuit by Judge Carlos Moore, who demonstrated the psychological effects of living in a state with a flag that upholds “state sanctioned hate speech.” In a room full of Mississippi flags and emblems that uphold the Confederate cause, a panel defines the word vexillology, the study of flags and their meanings. An interactive section invites visitors to use felt pieces to design their own flags. Yet the exhibit does not mention Moore’s lawsuit, other objections to the flag, or the fact that a new flag design is already being used by many state institutions that are tired of waiting for change. I wished the history museum did more to expose the current challenges that African Americans face in the state.

Jere Nash, a Jackson historian, says that it isn’t the role of a museum to speak to or solve current issues in the state. “That’s the role of a lot of other people and organizations. The museum’s sole task is to tell the history of a certain period.” Still, a well-curated museum, like a church, can play a pivotal role in expediting individual and societal healing. A space is prepared for listening and honest storytelling. People may experience small epiphanies that effect change outside the walls.

Jackson’s two museums hold relics of bone, hair, and blood that connect visitors with Mississippi’s saints and sinners. In the history museum, a Civil War showcase holds a small replica of a Bible that a Confederate soldier carved from a piece of human bone. Looking at that little carving, I wondered if it came from the body of a man who’d died to uphold or resist slavery. Then I felt a twinge of something like mercy: some lonely soldier had carved a Bible out of human bone and my first thought had been to ask whether it was an “enemy bone.” That tiny bone Bible gave me pause as I remembered the words of the Irish poet Pádraig Ó Tuama: “Peace that comes through the annihilation of the enemy is no peace at all.” I thought about how the Bible continues to be a central tool in narratives of oppression and liberation. I found myself praying for a deeper peace, a peace to the bone, deeper than this country has ever known.

Perhaps the closest I came to feeling a sense of peace was in the room that displays artifacts of Mississippi’s first people. The only sounds are water lapping against a 500-year-old dugout canoe and recorded bird songs. I found respite in the quiet of those simulated woods.

But I also knew that after 1830, the majority of the old-growth forests were cleared and transformed into cotton plantations that were worked by enslaved Africans. After the war, cotton farming and logging continued to deplete the land. An exhibit about the great flood of 1927 shows how natural and political forces combined to fuel a mass exodus out of Mississippi and birth a generation of blues songs about broken levees. Recent efforts at reforesting Mississippi, rethinking a lost agrarian economy, and developing urban centers show that even the wounded landscape has a long way to go toward healing.

The civil rights museum bursts with so many printed stories, photos, and relics that I found myself drowning in information overload. I fixed my gaze on a small handmade treasure. A Freedom Rider named Carol Ruth Silver, who had been among the many people imprisoned at Parchman Farm Penitentiary, had used discarded soft white bread and spit to mold a complete chess set, the darker pieces stained with prisoners’ blood. The room that holds the chess set is lined with the mug shots of hundreds of Freedom Riders who endured beatings, insults, slander, spit, and imprisonment at the hands of a state government that held unflinchingly to its belief in white supremacy. These riders and voting organizers, who were called “outside agitators,” joined local activists and filled Mississippi jails to overflowing, forcing national attention on abuses that had long been ignored when the only victims were black. There, in the bloodstained bread, were the riders’ bodies—broken for me, for all of us.

Equally haunting were the artifacts from murders and acts of terrorism in Mississippi: the decommissioned 1917 World War I rifle that was found at the scene of Medgar Evers’s murder, the front of Bryant’s grocery store where 14-year-old Emmett Till allegedly whistled at a white woman and lost his life because of it, the charred remains of crosses burned in activists’ and pastors’ front yards. I found myself repeating “Lord, have mercy” in the presence of the wood and steel, as though I were walking the stations of the cross. Amid this violence, ordinary citizens continued to gather, pray, write, and resist. Their yellowing letters, petitions, articles, and declarations bear witness to the power of the spirit and the word.

The hall devoted to the lynching era is appropriately unnerving. Long black panels list the names and dates of every documented lynching in Mississippi, while Klan costumes, slogans like “America for Americans,” iron chains that held incarcerated men and boys in prison camps, and signs that upheld segregation line the ceiling and walls. Uncomfortable silences are punctuated at irregular intervals with recordings of menacing voices, “What are YOU doing here?” and “We don’t serve your kind,” accompanied by the ring of a cash register, slamming screen doors, and a barking dog. It creates a nightmare effect that made me want to get out. I watched an elderly woman sit in that space and talk back to the stream of voices. With arms crossed and head held high, she turned to her companion: “Hmph! What am I doing here? I’m sitting down and taking a rest, that’s what I’m doing here.”

As a counterbalance to the heaviness of most of the civil rights museum’s content, every 30 minutes a colorful sculptural ribbon of lights illuminates the central atrium while the song “This Little Light of Mine” resonates through the entire museum. One time, when the music stopped, I heard the voice of a young girl continuing the song. “Mine, mine, shine, shine,” she kept singing and clapping, her joy unfettered. Amid so many examples of human courage and cruelty, held in that great cloud of witnesses, her voice was a call for lasting peace.

I was drawn to a panel that described African American farmers, whose land ownership nationwide peaked at 15 million acres in 1910. An elderly man wearing a purple family reunion T-shirt leaned against his walker and said to me, “That was me. I was a farmer. Corn, melons, okra, beans, hogs, chickens, cows: we raised everything we ate. The only thing we bought was rice; the ground wasn’t wet enough for rice.” He described how they used a mule-driven press to crush sugarcane to make green juice: the froth would be made into beer and the liquid would slowly cook down to sticky black syrup. I asked him what happened to his family farm. He didn’t go into detail, but by the time he had completed his military service in Vietnam, the 100 acres that his family had faithfully tended were no longer in the family. “I guess I’ve been in the city ever since,” he remarked, much like a refugee aching for a homeland to which there is no return.

An unexpected treasure of the civil rights museum was listening to other visitors pour out their stories, like water from a well-primed pump. The history museum felt quieter and more reserved. I didn’t hear anyone there talking back to the exhibits or sharing their stories aloud. While the history side felt spacious, the information on the civil rights side felt densely packed, as if the two museums were a small taste of the differences between living in urban and rural spaces. Standing shoulder to shoulder with other visitors in the civil rights museum made me feel like we were all in it together. I left the museums feeling troubled and perplexed about the ongoing silences and spaces between us. Each museum closes with questions challenging visitors to consider, “Where do we go from here?”

After a whole day in the two museums, I was hungry and tired. My brother and teenage son were with me, and we were wondering where to eat. We were strangers in that town, and the museums had heightened my anxiety about where we belong. We passed a restaurant that only had white diners outside, and I did not want to be there. We drove away from pristine, luminous high-rises to the part of town where the buildings were collapsing and grass was growing on the sidewalk. There we found a soul food restaurant near the railroad tracks. After a satisfying meal that tasted like home, I asked the proprietors how they felt about their city’s new museums. They said they hadn’t visited and wanted to know what I thought.

I tried to sum up my mixed review. I felt traumatized, overwhelmed, and confused. The museums honestly portray how the state has sanctioned the violence displayed on the walls. But they fail to show the extent to which we are still living in an era of hate crimes, inequality, and xenophobia. I saw many black families taking it all in, but I really wished that more white families—especially the ones whose ancestors had fought for segregation—would visit, making it a priority to learn and truly repent.

Yet I felt gratitude for the museums’ emphasis on the ordinary people, student groups, and churches who had organized and resisted to the point of exile and death. It was clear that the movement was fueled by people of faith, which made me grieve how many churches were—and are—silent or complicit in government-sanctioned cruelty. The restaurant owner talked about how racism is still powerful but more hidden and therefore harder to resist than it was before. She suggested I talk to an elderly diner who was just finishing her supper.

Mrs. Ineva Mae Pittman, an 84-year-old retired Jackson public school teacher, set down her fork and told me about her involvement in the movement. She described how teachers were not allowed to be active members of the NAACP, yet she and others attended meetings across the state almost every evening. Pittman described being questioned by her school superintendent after a mass meeting in Jackson and the careful wording that she and other teachers used to outsmart the officials, who conspired with local police to watch their every move. She was at a training session in Oberlin, Ohio, when the activists Andrew Goodman, Michael Schwerner, and James Chaney went missing. Pittman described her sinking feeling that the men were already dead, even as Schwerner’s wife begged for everyone to call their representatives and demand an investigation.

When I told her I had just visited the new museums, Pittman said, “We wanted it in Tougaloo or in the black community.” For her, downtown Jackson held too many painful memories and associations. “I haven’t been; I don’t plan to go there. I don’t say my mind won’t change, but I don’t plan on going.” The first people to invite her to be involved in the opening of the museum were two white men who had no connection to the movement, as far as she was concerned. She felt as though they wanted to use her and her influence in the black community to get more people to come, so she refused, asserting, “I was always independent of the power structure.”

I talked with Pittman a bit more about the troubled history of racism. I couldn’t understand how the president could have been invited to speak at the opening of the museums, which she and many other activists refused to attend. She leveled her gaze at me and said simply, “That is the Mississippi way of life.”

After the runoff election, as Espy spoke in the civil rights museum, in the shadows of men and women who died to defend human rights in their state, he said of his opponent, “She has my prayers as she goes to Washington to unite a very divided Mississippi.” He urged his supporters to “continue to believe” and keep up the ongoing movement “for a Mississippi where everyone, regardless of race, party or religion feels their worth.” The bandage may be off, with the wounds seeing the light of day, but the healing is still a long time coming.

A version of this article appears in the print edition under the title “Reckoning with racism.” The author's visit to the museums was supported in part by a grant from the Louisville Institute.